The juxtaposition of the world-system/world system perspectives and its variants

V. Reflecting back on the perspective and variants

This unit is utilized to summarize the juxtaposition of the world-system/world system

perspectives and its variants on the one hand and the ‘Nepal texts’ on the other. It is intended as

an exercise in linkaging the theoretical and the empirical and in cultivating a habit of theoretical

thinking. It is expected that the colloquium will be summarized, documented, shared, and utilized

as a learning device during subsequent semesters in Kirtipur and other campuses.

### V. Reflecting Back on the World-System Perspective and Variants in Relation to the Nepal Context

This final unit seeks to juxtapose the **world-system theory** with the specific socio-economic realities of Nepal, as examined in the previous texts. By linking theoretical insights from **Immanuel Wallerstein’s world-system perspective** and its critiques to empirical evidence from Nepal’s development trajectory, students are encouraged to reflect on how global systems of inequality manifest in local contexts like Nepal. The ultimate goal of this reflection is to cultivate a deeper understanding of **theoretical thinking** and apply it to empirical data.

#### 1. **World-System Theory and Its Key Concepts**

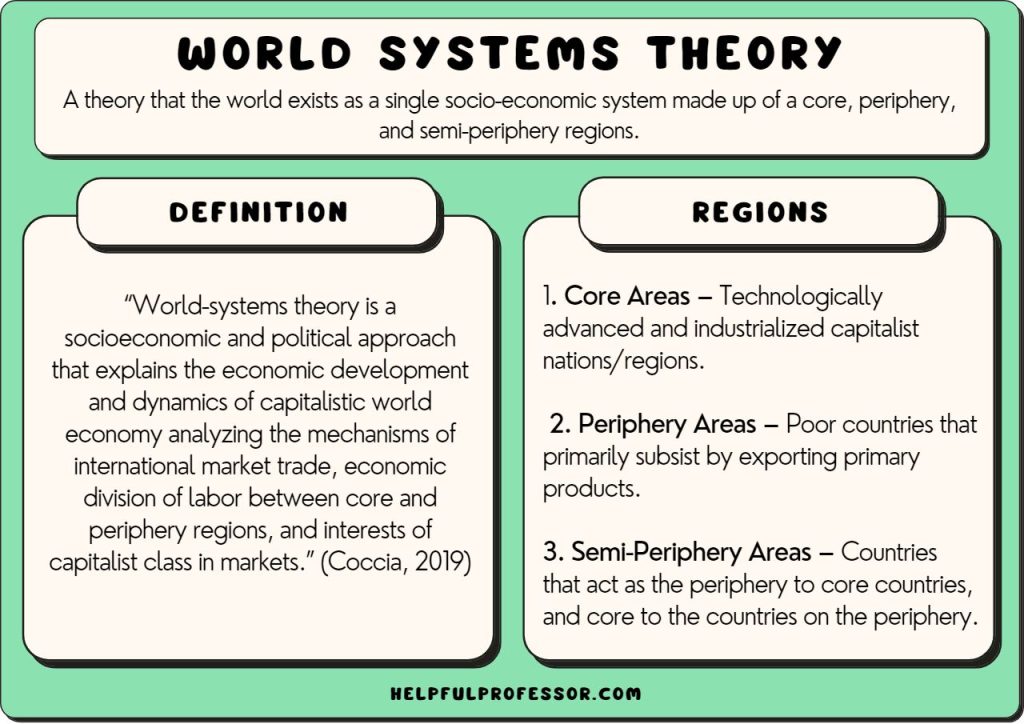

At the heart of Wallerstein's **world-system theory** is the idea that the modern world is organized into a global economic system characterized by unequal relations between a **core**, **semi-periphery**, and **periphery**. The core nations dominate the global economy, controlling **capital**, **technology**, and **high-skill labor**, while peripheral nations provide **cheap labor** and **raw materials**, often becoming dependent on the core for economic survival. Semi-peripheral nations act as intermediaries, experiencing both exploitation and some degree of upward mobility.

This framework emphasizes the role of **capitalism** in creating and perpetuating global inequalities, where countries in the periphery are continually exploited for their resources, labor, and markets. Wallerstein’s model, however, has been critiqued for being too **economically deterministic** and for minimizing the role of local actors, **state institutions**, and historical contingencies in shaping developmental outcomes.

#### 2. **Nepal as a Case Study of Peripheral Status**

The empirical case of Nepal, as discussed in the **Colloquium on Nepal**, provides a concrete example of a country situated in the **periphery** of the global capitalist system. Authors like **Piers Blaikie, John Cameron, and David Seddon** describe how Nepal’s peripheral status shapes its economic stagnation and dependence on foreign aid, mirroring many of the dynamics described by Wallerstein in his world-system theory. The **agrarian crisis**, **low productivity**, and **limited industrialization** position Nepal firmly as a peripheral nation, where external forces and global economic shifts exert a significant impact on local economic realities.

Nepal’s reliance on **remittances** and **foreign aid** further exemplifies its dependency, as global labor markets shape both internal migration patterns and economic development strategies. In this sense, the **unequal economic exchanges** described by world-system theory are vividly reflected in Nepal’s development trajectory.

#### 3. **Critiques and Variants of the World-System Theory**

The critiques of world-system theory, particularly those from scholars like **Theda Skocpol**, **Andre Gunder Frank**, and **Christopher Chase-Dunn**, offer important nuances that help explain Nepal’s unique development challenges. For instance, Skocpol’s critique of Wallerstein’s **overemphasis on economic factors** and **neglect of state institutions** is relevant to Nepal, where political instability, internal **class structures**, and **caste hierarchies** play significant roles in shaping developmental outcomes. Skocpol’s focus on **state autonomy** could help explain why Nepal, despite its peripheral status, has seen moments of political transformation and social movements that challenge external domination.

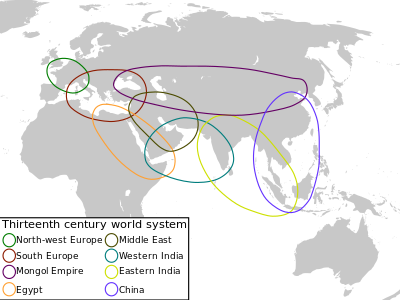

Similarly, **Andre Gunder Frank’s** argument for a **5,000-year world system** highlights the importance of long-term global trade networks, particularly in Asia, which may offer a broader historical context for understanding Nepal’s development. Nepal’s economic history, including its **trade relations with India** and its position as a mediator between **China and India**, might be better understood through Frank’s emphasis on **historical continuity** in global systems rather than the more rigid break proposed by Wallerstein in the 16th century.

Additionally, **Chase-Dunn’s** call for recognizing both **continuities and differences** in world-systems across time is particularly helpful for Nepal. Nepal’s internal development challenges are not solely the result of its integration into the modern capitalist world-system but also reflect long-standing **social, political, and geographical factors** that have shaped the country's position in the world economy over centuries.

#### 4. **Local Specificities: Insights from Chaitanya Mishra and Other Nepalese Scholars**

Chaitanya Mishra’s work adds a crucial **local perspective** to the world-system framework, emphasizing the internal social structures—such as **feudal land relations**, the **caste system**, and **elite dominance**—that perpetuate underdevelopment in Nepal. Mishra’s arguments are aligned with the **dependency theory** critique of world-system analysis, which focuses more on **internal class dynamics** within peripheral nations.

Mishra’s critique of **external dependency** through remittances and foreign aid resonates strongly with Wallerstein’s model but also underscores the **agency of local actors** in shaping Nepal’s development path. While global forces are undoubtedly influential, Nepalese elites, political leaders, and social movements have also played a role in the country’s development trajectory, sometimes exacerbating inequality and at other times challenging the status quo.

The work of **Ian Carlos Fitzpatrick** on the **cardamom economy** in a Limbu village and the policies governing **labor migration** further illustrate the **interplay between local and global forces**. Fitzpatrick’s ethnographic work shows how global markets affect local livelihoods and how local class structures are transformed by participation in global trade. This aligns with the world-system analysis but also highlights the **agency** of local actors in navigating these global dynamics.

#### 5. **The Theoretical and Empirical Linkages**

Linking the theoretical framework of world-systems theory to the empirical case of Nepal provides important insights into the nature of **global inequality**, **local development**, and the **role of peripheral nations** in the world economy. While world-systems theory offers a **macro-level explanation** of global inequality, the case of Nepal emphasizes the importance of **internal social structures**, **political institutions**, and **historical legacies** in shaping development.

For instance, world-system theory helps explain why Nepal, as a peripheral nation, struggles with economic stagnation and dependency on external aid. However, it is local factors—such as the **agrarian structure**, the **role of elites**, and the **political instability**—that complicate the picture and require a more nuanced understanding of development.

Moreover, the **critiques** of world-systems theory, particularly those that emphasize the role of **state autonomy**, **internal class dynamics**, and **historical continuity**, offer valuable insights for understanding Nepal’s particular challenges. While global forces shape Nepal’s economy, the **agency of the Nepalese state**, its **elite classes**, and the broader **social structure** are also key factors in determining the country’s developmental trajectory.

#### 6. **Concluding Reflection**

The juxtaposition of **world-system theory** with the **Nepal texts** encourages a deeper engagement with both **theory and empirical data**, allowing students to develop a habit of **theoretical thinking**. By examining how global systems of inequality manifest in a specific national context, students are better equipped to understand the complexities of development in peripheral nations like Nepal.

The colloquium’s exploration of these themes underscores the value of integrating **macro-level global analysis** with **micro-level local studies**. This exercise not only broadens our understanding of **global capitalism** and **world systems** but also highlights the **importance of local specificities** in shaping national development outcomes. As this colloquium continues to be shared and utilized in future semesters, it serves as a vital tool for fostering critical thinking and analytical skills among students studying **development sociology** and **global inequality** in Nepal.

In conclusion, reflecting on both the **world-system perspective** and its variants, alongside the **Nepal texts**, helps students see the intersection between **theory** and **reality**, providing a framework to analyze contemporary society and development in Nepal within the larger global system.

.svg/459px-World_Systems_Theory_(Dunaway_and_Clelland_2015).svg.png)